|

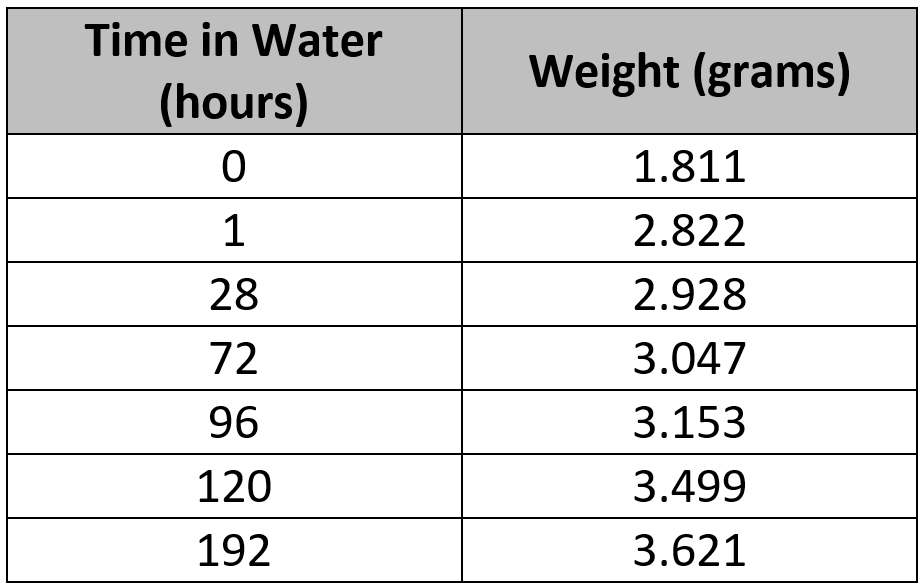

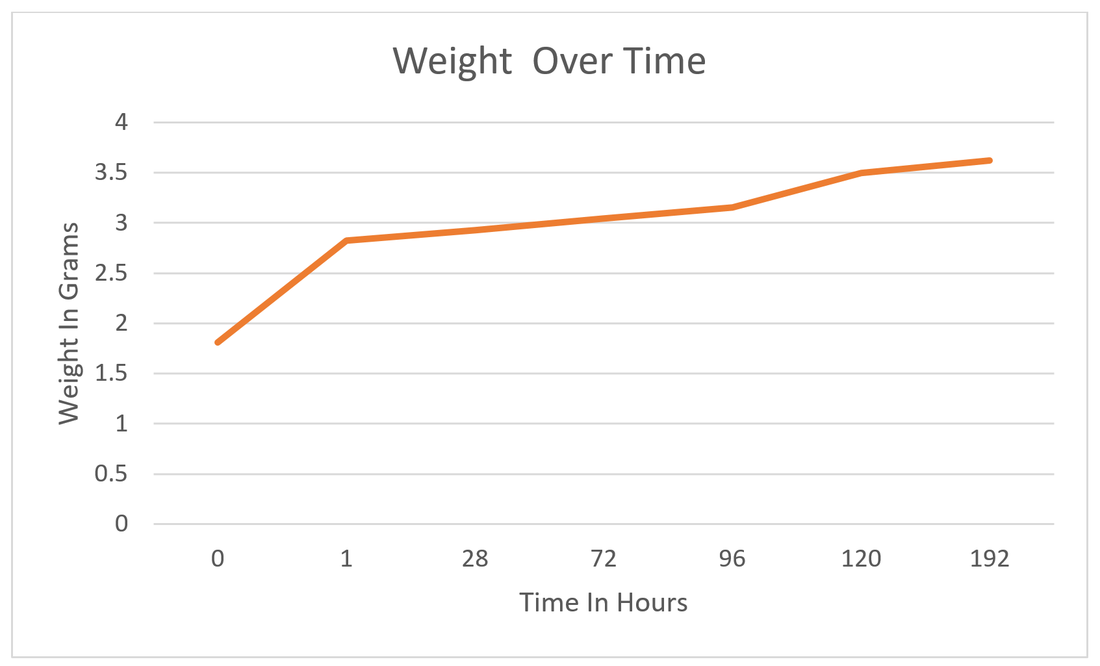

As I mentioned in the previous post, there are virtually limitless options when it comes to foam. So, what foam should you use for flotation in your boat? It can be perplexing, but hopefully after reading this you’ll have a better idea about adding flotation to your boat. Should you even use foam at all? I’ve seen quite a few people (though definitely a minority) argue that foam floatation is just a hassle and, if you aren’t required to, you should just skip it. They argue that regardless of the foam you use, it’s going to absorb water, and it’s going to take up space. Floatation foam is designed to keep your boat at the surface with water up to the gunnels, but “they” would argue that the boat would still be a total loss having been submerged (clearly, judging from my boats, we have a different opinion of what constitutes a total loss). Obviously, I think “they” are wrong; not because the boat can be salvaged, but for safety. “They” will say they have a life jacket, so it’s no big deal, but as anyone that has done man overboard drills with a dummy knows, it’s a lot harder to spot a person floating in the water than you might think (even if their head is orange). It’s a lot easier to spot an overturned or partially submerged boat than it is to see a person. Aside from that, a partially submerged boat also provides shelter and a means to get yourself up and out of the water, which makes a substantial difference in survival time. So, the answer for me is, yes you need foam. The federal government agrees with me and per USCG requires all new boats under 20-ft to have integral floatation that will provide at upright and level floatation when fully filled with water. I’ve seen a few people argue for the use of sealed flotation compartments or just filling compartments with sealed bottles. They point to the fact that these flotation methods won’t get waterlogged like foam can, but the counter argument is that they aren’t as reliable as foam. Granted anything that will displace water in a large enough volume to float your boat will work for flotation. Foam provides a more resilient flotation, whereas a sealed compartment or 4 sealed milk jugs have a greater possibility of failure. Even if you damage a block of foam (break it in half, stab it with a knife, etc.), it will still provide significant buoyancy. Whereas, if you poke a hole into a sealed compartment filled with air, it will lose all its buoyancy, and poking a hole in one of the 4 milk jugs will result in losing a full 1/4 of your buoyancy. That is why I prefer foam, but I am not vehemently opposed to other methods. Now you just need to figure out what type and how much foam you need. Should you use polystyrene or polyethylene or liquid urethane foam or something else? There’s no shortage of choices and I’m not going to give you a definitive answer on which one is the best; they all have strengths and weaknesses. You need to look at their respective properties and see which one is going to fit your needs the best. The most common foams I’ve seen are the above listed polystyrene, polyethylene, or poured liquid urethane foam. Any of these should work fine, the most important thing is to use a closed-cell foam and ensure you have enough of it to float your boat and gear. Foam is made up of bubbles; in the case of closed-cell foam, those bubbles haven’t popped and thus won’t absorb moisture. Open-cell foam is like a sponge and will be useless in providing floatation for your boat. Now, to the point that any foam will eventually become waterlogged, that is largely due to improperly storing your boat or poor installation of the floatation foam in the first place. If you allow the foam to sit in water, it will eventually break down and absorb water (water is the universal solvent). In installation, you want to make sure that the foam is placed such that water can drain away from it and doesn’t become trapped (e.g. limber holes). When you store your boat, make sure the water has somewhere to go by pulling the bilge plug and raising the bow so that water will flow down and out the bilge. Even a closed cell foam has voids between the cells and will absorb some water. As an experiment I took a piece of packaging Styrofoam (polystyrene) and submerged it for a week to see how much water would be absorbed over time. The 3-in by 1.5-in by 0.5-in piece of foam initially weighed about 1.8-grams. I placed it into a tub of water and placed a water bottle on top of it to keep it submerged. The table below shows the time that the foam had been in the water and the weight at the time. After an initial rapid weight gain, which is a result of water making its way into the rather large voids within the foam, the weight changed more gradually as the water worked its way deeper into the smaller voids. After a week of soaking it had doubled in weight, gaining an additional 1.8-grams of water, which is about half a teaspoon. Removing it from the water and letting it dry for 24-hours returned it to the starting weight of 1.8-grams and a subsequent dunking provided similar results. So, the longer you let it sit in water, the more water will be absorbed and the more difficult it will be to fully dry out. This is more of a concern in cold climates, with freezing temperatures in the winter. Any trapped water will freeze and rupture the closed-cells of the foam. It then thaws and is absorbed into those now open-cells only to refreeze and do more damage to the foam. As this freeze thaw cycle continues the foam breaks down and will eventually become saturated with water. Keep it dry when you’re not using it (i.e. your boat sank) and it should be fine. Now, we just have to calculate how much foam you need to float your boat. The first step here is to figure out how much weight you need to float. You can do this three different ways (more really, but these are the most realistic):

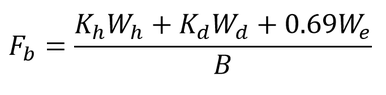

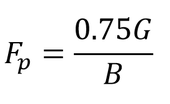

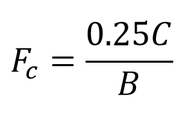

Once you have this total weight, it’s a relatively simple matter to calculate the volume of foam you need to float it all. You can use the formulas from the USCG boat builder’s handbook (http://uscgboating.org/regulations/assets/builders-handbook/FLOTATION.pdf) to determine the amount of flotation needed. Fb is the volume of flotation needed for the boat hull, Kh and Kd are conversion factors for the materials used for hull and superstructure (0.33 for aluminum), Wh is the weight of the hull, Wd is the weight of other structural components, We is the weight of any equipment or gear, and B is the buoyancy of one cubic foot of the foam being used. Most flotation foam has its density represented as the weight of a cubic foot of the foam. Usually, flotation foam is 2-lb foam; so a cubic foot of foam would weigh just 2-lbs and displaces a cubic foot of water, which weighs about 62-lbs. Thus that foam provides 60-lbs of flotation, which is your value for B in these equations. In the Lone Star’s case, I got approximately 1.667-cuft of foam for the boat and associated gear. Fp is the volume of flotation required for propulsion equipment and G is the weight of the engine, battery, and associated equipment. With an engine and battery weight of nearly 200-lbs on the Lone Star, I got a value of 2.5-cuft. Fc is the flotation required for the personnel capacity and C is the maximum weight capacity. With a planned capacity of 4 people at 150-lbs each (I wish, but my wife offsets my extra cushioning), I ended up with a value of 2.5-cuft.

Once you have these values you simply add them all together to get the total required flotation requirement (in my case 6.667-cuft). In total, I actually have almost 8-cuft of foam packed in the Lone Star between the bow, the benches, and the transom. The trick really is figuring out where to put it. Now I just hope that I never need it. Until next time, here’s wishing you fair winds and following seas.

1 Comment

3/21/2022 23:11:07

This blog is extremely informative. Thank you for providing the graphs to make it easier to understand.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorBrent Pounds has over a decade of experience in the maritime industry and has been involved in recreations boating since he was a child. See the About section for more detailed information. Archives

October 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed